New York City real estate developer Gerald Wolkoff has appealed the $6.75M judgment in favor of the 20 artists’ whose work he whitewashed before demolishing his iconic Long Island building in 2013.

Wolkoff’s lawyer, Meir Feder, argued before New York’s 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals on Friday that Judge Frederic Block wrongly interpreted the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act in his November 2017 ruling when he determined all 45 pieces of art on Wolkoff’s 5 Pointz building were protected under VARA.

The 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) provides federal protection for distinguished works of art by enabling artists “which provides federal protection for distinguished works of art by enabling to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work” and “prevent any destruction [of their work].”

“Courts cannot be assessing the merits of works,” Feder said while explaining the use of VARA needed to be limited, especially when it comes to graffiti, which is “temporary in nature.” Furthermore, Feder said Block’s ruling opened the door for any aerosol artist to invoke VARA any time a real estate developer decides to modify or demolish a building with their artwork on it.

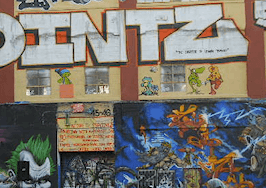

In 2013, Wolkoff whitewashed his 200,000-square-foot building on 45-46 Davis Street in Long Island’s 5 Pointz area before demolishing it in favor of building an apartment complex. According to a previous Inman report, Wolkoff was a rare developer who allowed artists to cover his building in graffiti and large-scale murals, which attracted tourists and locals alike.

The first artists began painting the building in 1993, with many of them repairing or completely repainting their works over the years. But, an official contract between Wolkoff and the 20 artists was never signed, according to court documents.

Judge Block said in 2017 that Wolkoff denied the artists an opportunity to preserve their works, despite knowing about VARA. And because of that, he owed $6.75M in damages to the artists who used his building.

“The sloppy, half-hearted nature of the whitewashing left the works easily visible under thin layers of cheap, white paint, reminding the plaintiffs on a daily basis what had happened,” wrote Block. “The mutilated works were visible by millions of people on the passing 7 train.”

Second Court of Appeals Judges Barrington D. Parker, Raymond Lohier, and Reena Raggi seemed to be more sympathetic to Feder’s argument than Block was, noting there needed to be better legal guidance on how VARA should be invoked.

“Any squiggle by Picasso is going to have more stature than something I scribble here today,” said Judge Raggi while grappling with how to assign protected status to pieces of art. “How do you deter nuisance suits?” followed Judge Lohier while mentioning the $6.75M judgment handed down in February 2018.

The appeal is still being adjudicated, but Judges Parker, Lohier and Raggi’s decision could change the course of how real estate developers operate in cities such as New York City where buildings are often used as canvases.

Art lawyer Kate Lucas told Inman in 2018 that the argument over VARA will take time, since the Act has only been invoked during legal proceedings twice in 2006 and then in 2018. In the meantime, Lucas suggests that developers and artists sign contracts.

“Whether this is a sculpture that’s going to be in the courtyard or a mural on the wall, you can avert a lot of problems if you proactively work with the artist who’s doing the art for you and lay out ahead of time, ‘What happens if I sell the building?’” said Lucas.

“What happens if the work needs to be restored or is damaged and needs to be repaired? Do you want to do the repairs, or do I have the power to do the repairs? What happens if I want to take it down?”