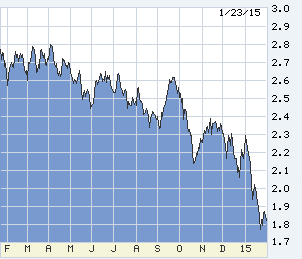

A wild story still unfolding, most of it overseas. The result here at home: mortgage rates near 3.75 percent and the lows of the year — and the tilt in chart-pattern witch-doctoring to lower yet. Rates will rise only on substantial good news, somewhere.

The only domestic economic data of note: Starts of new homes and sales of existing ones are flat. It is the dead of winter, after all, but mortgage rates are within an inch of the 70-year low. Rising rates was the leading (false) explanation for flat sales last year; now it is the absence of for-sale inventory. If we have demand but poor inventory, we would build, and we’re not. Save deconstruction of housing reality for another day.

There is some upward pressure on rates from the new wave of refis, which feel to markets like net-new sales of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Previous owners of MBS based on 4.5 percent-plus mortgages do not necessarily leap to buy ones paying almost 1 percent less. However, what else can they buy? And that mechanism is in play all over the world.

When U.S. MBS look attractive to investors — payments are guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae — that demand pushes their prices up, and yields down. Homebuyers and homeowners refinancing pay lower interest rates.

Doug Behnfield of UBS, a fine bond-investment manager, dredged up this old New York trading term: the “Gazinta.” A colleague or client proposes selling a position, and old-timers reply, “Yeah, what’s ya Gazinta?” Translation: Gazinta is the Brooklyn-mangled shorthand for “go-in-to.” You can sell, but unless you want to sit in cash, what will you buy? Selling is always easier than investing.

The U.S. 10-year Treasury trades 1.81 percent this morning, a fundamentally ridiculous Gazinta with the Fed intending to raise its rate by summer. However, German 10s trade 0.321 percent, and Japan’s 0.238 percent — and both the yen and the euro are crashing versus the dollar, which makes rich the dollar equivalent of our ridiculous Treasurys.

The bond-market Gazinta is driven by that currency Gazinta (patience, please — there is and end to this). The European Central Bank yesterday announced its long-awaited QE. It will fund the purchase of 60 billion euros’ worth of eurozone securities each month way into 2016. The “funding” will be provided to individual nation central banks pro rata to GDP, which means Germany, needing no help at all will get the same pro rata share as Italy, near its black hole. As public policy goes, pathetic.

QE1 here, announced November 2008, was nothing short of miraculous. Its focus was MBS, whose yield spread over Treasurys had risen from 1.8 percent to double that. QE1 righted a panicked and wrecked market, helping housing to bottom. QE2 18 months later pushed down long-term rates. QE3 in 2012 … the Fed knew in months was a diminishing return, ineffective, and backed out of it as fast as dignity would allow.

Europe’s QE will be less effective than QE3 here, possibly undetectable. The primary problem: Eurozone rates are already essentially at zero. Out to five years, many sovereign bonds there trade at below-zero yield. Thus the ECB will pour out a trillion euro cash in exchange for a trillion in cash.

Another ECB QE problem: few bonds to buy. U.S. bank assets are only about 75 percent of GDP, and the rest of our immense credit supply is securitized — MBS about $7 trillion by themselves. Europe (like Japan) is bank-centric. French bank assets are four times its GDP. European MBS markets are trivial.

The end of the Gazinta chain: The primary effect of ECB policy is to drive down the euro. A lower euro will make euro exports more competitive, and make imports more expensive, which should generate euro inflation. However, unlikely to work because the world is in a full-scale currency war, beggar-ALL-thy-neighbors. Last week the Swiss were forced to drop a euro peg, let the Swiss franc rise and accept the economic damage.

This week both Denmark and Canada were forced to act. Denmark desperately and foolishly trying to hold the kroner down to the level of the falling euro, cut its overnight cost of money to minus 0.35 percent. Canada is hurt by oil, and cut its overnight rate from 1 percent to 0.75 percent.

Two near-term mysteries: When will China have to drop its dollar peg to stay competitive with Japan and Europe? And when will the U.S. feel the effect of everybody devaluing versus the dollar? Meanwhile, U.S. mortgages are the Gazinta!

Lou Barnes is a mortgage broker based in Boulder, Colorado. He can be reached at lbarnes@pmglending.com.